Making Arguments with Impact

Jan 16, 2022

One skill that Savvy Directors are always interested in improving is their ability to make clear concise arguments. When their board is faced with a decision, they want to express their views on the issue and try to convince their fellow directors.

Having influence in the boardroom requires good communication skills, like active listening and knowing how to ask tough but fair questions. But sooner or later every director has to speak up – otherwise you might as well pack up and go home. And when you do choose to speak, you want to make sure your words have the impact you intended.

In the context of boardroom discussion, the word argument shouldn’t be seen as having a negative connotation. In fact, good, solid arguments are the basis of persuasive communication. You can think about them in the same way as a lawyer making legal arguments, or a debater presenting arguments for or against an issue. They’re intended to change people’s minds.

The boardroom is a natural home for arguments. In fact. the best boards enjoy a climate of robust debate where sound arguments – but not fights - flourish.

“In a fight, there is a winner and a loser. In an argument, the participants try to win over the audience by debating ideas, presenting facts, persuading, and influencing.” - Dr. Ann-Maree Moodie. The Art of Persuasion in the Boardroom

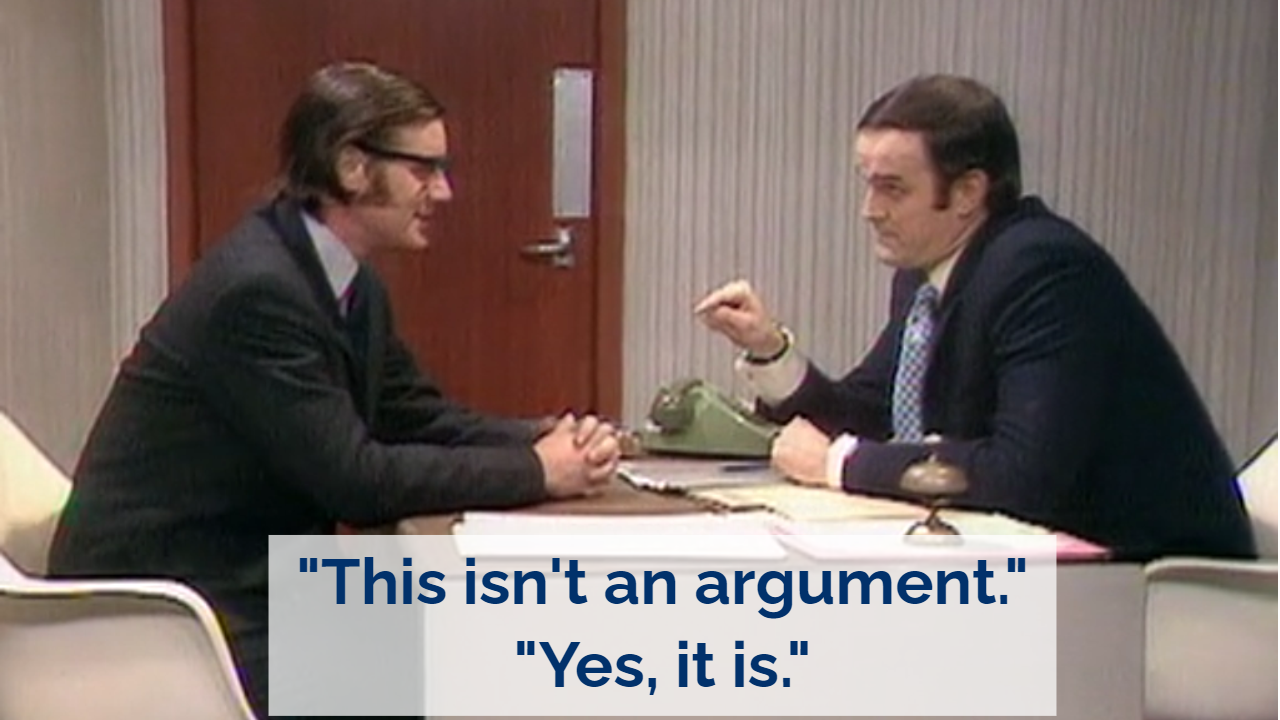

The Argument Clinic

Remember Monty Python’s Flying Circus? (For readers who are too young to remember, it was a British sketch comedy series that ran in the early 1970’s.) One of my favorite sketches was The Argument Clinic with John Cleese and Michael Palin. (Watch it on YouTube >>here<<.)

In the sketch, a man enters an office reception where he asks to have an argument. After a misstep into the Abuse Office, he finds himself in the Arguments Office. Hilarity and frustration ensue when it becomes evident that the two characters have very different conceptions of what an argument is.

The dialogue goes like this:

- Palin: Well, an argument’s not the same as contradiction.

- Cleese: It can be.

- Palin: No, it can’t. An argument is a connected series of statements to establish a definite proposition.

- Cleese: No, it isn’t.

- Palin: Yes, it is. It isn’t just contradiction.

- Cleese: Look, if I argue with you, I must take up a contrary position.

- Palin: But it isn’t just saying, “No, it isn’t.”

- Cleese: Yes, it is.

- Palin: No, it isn’t! Argument is an intellectual process; contradiction is just the automatic gainsaying of anything the other person says.

When your board is faced with a decision, let’s hope the arguments for and against don’t bear any resemblance to those of the John Cleese character! Instead, a director’s argument should conform more closely to the Michael Palin statements, “An argument is a connected series of statements to establish a definite proposition,” and “Argument is an intellectual process.”

The Structure of an Argument

When Michael Palin’s character says that an argument is ‘an intellectual process consisting of a connected series of statements that establish a proposition,’ that implies that a good argument has a structure. Experts tell us that an argument’s structure consists of one or more premise and a conclusion.

- Premises. A premise is something that is put forward as a truth. In a boardroom discussion, premises are the facts you’re relying on to support your viewpoint. They’re the building blocks of an argument, so you usually want to have more than just one (but not too many – people will lose track) in order to strengthen your argument. If you can, keep them short and non-controversial.

- Conclusion. The conclusion is the statement that you want others to agree with. It should flow logically from your premises. In a boardroom discussion, your conclusion expresses the decision that you think should be made, framed in a way to persuade others to agree with you.

Let’s look at a simple example. The board is discussing whether or not the organization should undertake a capital project at this point in time. You want to make an argument in favor of going ahead with the project now rather than waiting. The structure of your argument would be something like this:

- Premise 1. Interest rates are currently low.

- Premise 2. Interest rates are projected to rise.

- Premise 3. Inflation is increasing the cost of construction materials.

- Conclusion. It’s financially prudent to undertake the project now.

Between the conclusion and the premises is inference - the reasoning process that translates the premises into the conclusion. Inference – often unspoken and unwritten - might make use of careful logic, but it might just as well be based on emotional reasoning, assumptions, values, biases, and logical fallacies.

When you’re composing your argument – or evaluating someone else’s – it’s a good idea to try to bring the inferences to the surface and examine them to ensure they are valid. For instance, in the above example, there’s an unspoken assumption that the project under discussion is a good idea!

Simple Guidelines for Effective Communication

Of course, structure is just the starting point. When you have something important to say, the better you are at saying it, the more likely people are to understand and accept what you have to say. With this in mind, when there’s a board decision on the agenda, it’s best to mentally compose your arguments and make a few notes ahead of time, as part of your meeting PREP.

The Effectiviology article ‘Grice’s Maxims of Conversation: The Principles of Effective Communication’ outlines four principles that describe how people communicate to make sure they’re well understood. The first three have to do with what you say and the fourth has to do with how you say it.

As a board director, these simple guidelines will serve you well when you are putting your argument together.

Maxim One. Be informative.

- Be as informative as needed. In composing your premises, provide all the information necessary and don’t leave out anything important.

- Don’t be more informative than needed. Leave out unnecessary details that don’t add anything to the discussion.

Maxim Two. Be truthful.

- Don’t state anything that you believe might be wrong. If there is a compelling reason to do so, then provide a disclaimer pointing out your doubts.

- Don’t say anything that you can’t back up with supporting evidence, otherwise it’s just your opinion. If you feel you have to do so, point out the lack of evidence.

Maxim Three. Be relevant.

- Make sure that all the information you provide is relevant to the discussion.

- Leave out anything that is irrelevant – even if it’s interesting.

Maxim Four. Be clear.

- Don’t use jargon, acronyms, or language that’s hard to understand.

- Don’t use ambiguous language that’s open to different interpretations, making it hard for people to know exactly what you’re trying to say.

- Be brief and concise so that people will focus on the key details. Don’t over explain – there’s no need to repeat yourself. Try to eliminate meaningless phrases and filler words – use pauses instead.

- Provide information in an order that makes sense, making it easy for listeners to process what you’re saying.

If you’re thinking that these maxims seem almost trivial, you’re right. They’re fairly intuitive and really just follow common sense. But when you think about it, people violate them all the time without realizing it – in the boardroom and elsewhere.

Remind yourself to abide by these principles when you’re going to be making an argument in the boardroom. It takes a lot of work at first, but if you stick with it, you’ll find that the benefits are worth it and that it gets easier over time.

With these guidelines in mind, it’s useful to check over your prepared arguments and ask yourself the following questions. If the answer to any of the questions is no, try to make adjustments to ensure you’ll be making the impact you want.

- Have I included all the necessary information?

- Is my argument as concise as possible? Have I omitted unnecessary details and irrelevant information?

- Am I certain that everything that I’ll say is true, and can be backed up with evidence? If not, am I sure that it should be included? If so, have I provided a disclaimer showing my doubts?

- Is my language clear and unambiguous?

- Have I presented the information in a structured, well-organized, and logically ordered manner?

To be sure, there are times when you won’t have the opportunity to prepare your argument in advance. But if you make a habit of following these guidelines, they’ll become second nature. You’ll find you’re able to compose a good, solid argument in your head when you need to - one that adds value to the board’s discussion and makes the impact you intend.

Timing is Everything

If you want to make sure your words make an impact, waiting for the right moment can make all the difference. In the article ‘The Art of Persuasion in the Boardroom,’ Dr. Ann-Maree Moodie explains that successful boardroom debate has these features:

- Preparation: Everyone comes to the meeting well-prepared, having read the material thoroughly and compiled a list of a few key questions.

- Expression of views: The board chair encourages opposing views to be expressed then draws the discussion to a consensus position in the end.

- Good timing: A director chooses the right moment to ask the right question or inject a comment that lightens a tense mood or refocuses the discussion.

The right moment is likely to appear when board members are feeling uncertain and their minds are beginning to change. That’s what Dr. Moodie calls “a persuadable moment.” In a board meeting, it’s often after everyone else has spoken. If you have the patience to wait, you’ll have the opportunity to restate the comments that others made that support your argument, downplay the views you don’t agree with, and perhaps sway the board to your way of thinking.

Your takeaways:

- When stating your case in the boardroom, use a structure that starts with your premises and leads logically to your conclusion.

- For the most effective communication, practice being informative, relevant, concise, and clear.

- Choose the right time to make your case. Don’t be in a hurry.

- The better your arguments, the more you help build a climate of robust debate in the boardroom.

Resources:

- Grice’s Maxims of Conversation: The Principles of Effective Communication. Effectiviology.

- The Best Ways to Deliver Clear and Concise Communication. Beverly D. Flaxington. Psychology Today. October 2020

- The Art of Persuasion in the Boardroom. Dr. Ann-Maree Moodie, FAICD, FGIA, FCIS. © Governance Australia & Asia 2019.

- Boardroom Basics: 6 insider strategies to get your idea across the line. Nathan Chadwick, Tina Janamian, James Fielding, and Dr Sarah Kelly. Momentum. The University of Queensland Business School.

Leave a comment below to get in on the conversation.

Thank you.

Scott

Scott Baldwin is a certified corporate director (ICD.D) and co-founder of DirectorPrep.com – an online hub with hundreds of guideline questions and resources to help prepare for your next board meeting.

Share Your Insight: Can you think of a ‘persuadable moment’ in a board meeting that got missed?

Comment