Decisions, Decisions.

We all believe that groups make better decisions than individuals. There’s power in numbers, isn’t there? Otherwise, a board of directors might just as well consist of one person.

But is it true? Do groups really make better decisions?

How do groups go about making decisions, anyway? More importantly, how should they be making decisions to improve the odds of achieving the best outcome?

And what is the boardroom reality when it comes to decision-making? Do boards really make decisions? Or has management baked the cake?

Do groups make better decisions?

Group decisions often – but not always - produce better outcomes than individuals. They work best in situations where time is not a factor. The group method is not ideal when there’s an urgent need for a quick decision. A group’s advantages include:

- Drawing from the diverse backgrounds and perspectives of more individuals.

- Having the potential to be more creative.

- Being able to achieve results beyond what the members could have done as individuals.

- Making the task more enjoyable for people.

- Ease of implementation because group members are more invested in the decision.

The decision-making process

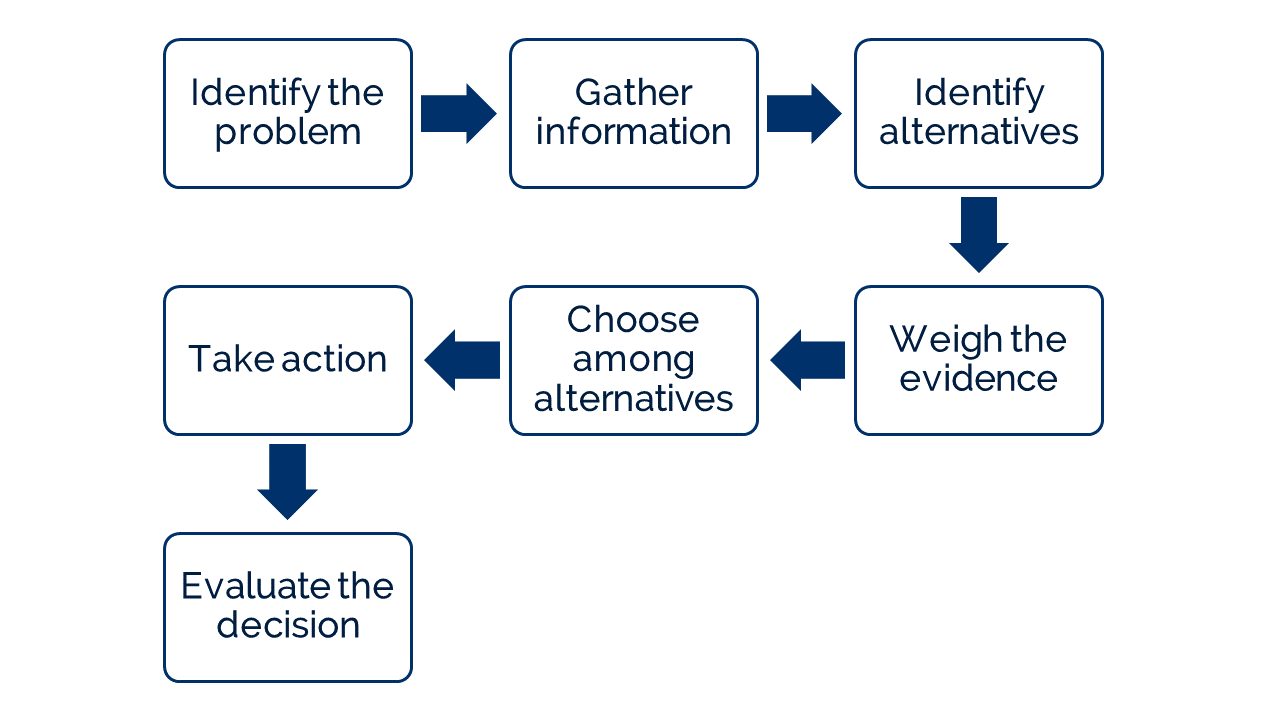

Years ago, I used to teach a course in problem-solving and decision-making. The course introduced participants to a basic group decision-making process along the lines of the one mapped below:

This type of process – logical, rational, evidence-based – is likely familiar to you. In courses like mine, managers were taught to rely on a structured process like this one, or some variation of it, to make important decisions. Research shows that using rules and processes to make important decisions yields a better chance of a positive outcome.

“Superb analysis is useless unless the decision process gives it a fair hearing.” - Dan Lovallo and Olivier Sibony, ‘The Case for Behavioral Strategy,’ McKinsey Quarterly 2010.

There are some important situations where the board would be well served by a formal decision-making process – decisions about governance-related matters for instance, or areas where management has an inherent conflict of interest, such as decisions about compensation.

And, of course, one of the board’s most significant decisions – selecting a CEO – often takes place using exactly this kind of process.

But for the most part, this ideal process does not really describe what happens in the boardroom. For a great many decisions, directors expect that this process has already unfolded within the ranks of management before a recommendation comes to the board for approval.

When the board is faced with a management recommendation, the options are pretty much limited to approving it as presented, approving it with revisions, sending it back for more work, or outright disapproving it.

How does the board proceed to make a decision then? The board’s role is to bring a different perspective to the problem at hand. The board is required to see the bigger picture, take a longer-term view, and consider the issue through the lens of risk.

In doing so, directors need to rigorously examine not just the final recommendation, but also the process that management followed, the inputs they considered, the criteria they used, and the rationale for making their selection.

“Because boards of directors don’t usually do their own analyses but rely on management teams to present them, the decision-making processes focus on asking challenging questions, playing devil’s advocate, and helping management come up with alternatives.” – Suzanne Nimocks, board director and former McKinsey partner, from Boards and Decision Making. McKinsey & Company.

Once the board has finished with its due diligence, it’s time to make the final decision. Boards use both consensus-building and voting to make their decision.

Decision by majority rule is simple and fast, and it’s generally perceived to be fair. It does have a downside, though - those who did not vote in favor of the decision are less likely to support it. (See our blog "Why support a decision if I disagree?" for more on this topic.) Depending on the nature of the decision (not to mention the personality of the board member!) that lack of support can pose a lingering problem for the board.

That’s why boards often strive for consensus before taking a matter to a vote. Working toward consensus helps gain support for a plan of action and maintain social cohesion, but it does take more time. This approach is inclusive, participatory, and cooperative. The ideal end to the process is to reach a decision that each member can live with. In the end, members may be frustrated with the outcome, but at least they feel they’ve been heard.

Going off the rails

The group process can go off the rails in so many ways. That’s not to say that board decisions are necessarily disastrous (although some famous ones have been!), but they are complex.

I was once party to a board decision that went off the rails just as the board had worked through an inclusive discussion, considered diverse alternatives, and was about to decide on a course of action. At that point, a single director spoke up – a well-respected director with influence and the gift of persuasion – who suggested one more potential course of action, along with an emotional appeal.

Presto! In an instant, the majority of directors abandoned their logical, rational choice and selected the last-minute option instead. Something had just happened to impair the quality of the group decision. (And, unsurprisingly, the outcomes were less than ideal.)

So, what are some of the pitfalls? They tend to fall into these buckets: information gaps, blind spots, process issues, structure, and culture.

Information gaps - The simple fact is that boards can rely too much on management presentations without probing for more information. Boards tend to focus on the information that’s presented to them rather than access the full range of relevant, available information. Economist Daniel Kahneman uses an acronym to describe how we use the information we have as if it is the only information: WYSIATI —what you see is all there is. It means that we make do with what we already know instead of asking ‘What else do we need to know?’

Blind spots - Our cognitive biases and mental shortcuts create blind spots that interfere with the quality of our decision-making:

- Groupthink. When directors value group harmony over critical thinking, individuals tend to refrain from expressing doubts. They reach premature consensus and make less-than-optimal decisions. See our blog Banish Groupthink from the Boardroom for more on this topic.)

- Anchoring. When directors hear the responses of others before providing their own, the first one sets the tone and subsequent responses tend to cluster around it.

- Confirmation Bias. Directors seek out information that validates existing views, and they fail to seek out disconfirming evidence or they explain it away.

- The Halo Effect. Directors have an unrealistic level of confidence based on the company’s prior success without considering how market forces influenced that success.

“Having a wide variety of views and concerns is great in theory, but in practice boards often behave like herds. Groupthink, as one researcher puts it, has contributed to the greatest corporate scandals of the last decades.” – Helen Lee Bouygues, Three Secrets to Smart Thinking on Boards and Other Teams, Forbes.

Process issues - Allowing insufficient time for proper consideration afflicts many board decisions. It always amazes me how the board can spend oodles of time on relatively minor items, then squeeze the most important decision into the last half-hour of the meeting. This tendency is so common that it even has a name – bikeshedding. (Click here to discover the origin of the term.) Big, important decisions should not be made quickly – whenever possible the process should extend over a number of meetings. (See our blog Soak Time on the Board for more on this topic.)

Structure - Inappropriate delegation of authority is another barrier. Whatever can be handled by management, should be delegated. Management is in the best position to make quick, agile decisions in the face of urgent requirements. The board can, and should, reserve its time for decisions that need board engagement. A lack of clarity around committee mandates can present the same kind of problem, creating confusion as to exactly what can be decided by a committee versus the full board.

Culture - It’s becoming increasingly clear that a board’s culture and interpersonal dynamics measurably affect the quality of its decisions. Issues that impair decision-making include a lack of diversity, quashing dissent instead of encouraging it, poor listening skills, lack of trust between board and management, and subtle or direct conflict among board members.

How boards can improve their decision-making

The Forbes article Three Secrets to Smart Thinking on Boards and Other Teams summarized the advice to boards quite succinctly - ‘Don’t be a rubber stamp, Leave no stone unturned. Value dissent.’

Here are a few practical ideas that some boards have used successfully:

Don’t be a rubber stamp - bring in more perspectives

- View the decision through the lens of risk.

- Consider the bigger picture and the longer-term.

- Appoint a panel of external experts with different points of view to hash it out, then excuse the folks who are not decision makers.

- Bring in a broad set of voices - individually, not together - and ask them about likely reactions to a potential course of action.

- Bring in experts you wouldn’t normally find within the organization.

Leave no stone unturned - get more information

- Conduct independent research or ask for new evidence.

- Direct consultants to develop different scenarios and provide alternative courses of action.

- Bring in outside speakers.

- Review the research and bring in specialists to explain it.

- Ask for information about the soft issues, not just the hard data.

Value dissent - strengthen the process and the culture

- Consider multiple options, not just management’s recommendation.

- Assign a devil’s advocate.

- Explore assumptions – both conscious and subconscious.

- Pose different scenarios.

What a Savvy Director can do

One of the best things an individual director can do is ask questions that keep the board from going off the rails. Questions like:

- What else do we need to know?

- What are our blind spots?

- Do we need more time? (Do we have more time?)

- Have we heard all the voices?

- Are there other options? (Have we considered all the options?)

- How will we evaluate our decision?

Your takeaways:

- Most board decisions involve evaluating a recommendation made by management. The board adds value by considering the bigger picture, taking the longer-term view, and seeing the issue through the lens of risk.

- Pitfalls in board decision-making include information gaps, mental blind spots, process issues, structure and board culture.

- To improve board decision-making, don’t be a rubber stamp, leave no stone unturned, and value dissent.

- To add value to board decision-making, don’t hesitate to ask great questions such as ‘What else do we need to know?’

Resources:

- Boards and Decision Making. McKinsey & Company. April 2021.

- Three Secrets to Smart Thinking on Boards and Other Teams. Helen Lee Bouygues. Forbes. March 2021.

- Decision-making in the Visionary Boardroom. Women Corporate Directors in partnership with KPMG. 2018.

Leave a comment below to get in on the conversation.

Thank you.

Scott

Scott Baldwin is a certified corporate director (ICD.D) and co-founder of DirectorPrep.com – an online membership with practical tools for board directors with a growth mindset.

Originally published July 25, 2021

Share Your Insight: What techniques have you observed for improving board decision-making?

Comment