Engaging with Your Stakeholders

Stakeholders are persons or groups with an interest in an organization who can affect or be affected by its decisions and activities. Given what’s happening in our world, it should be no surprise that the idea that organizations should be accountable to a broad base of stakeholders has gained traction, pushing the topic of stakeholder engagement to the top of many board agendas.

After all, our organizations don’t exist in isolation. They are influenced by the same forces of change that we’re all dealing with – forces like COVID-19, climate change, truth and reconciliation, social justice, activism, and so on.

Increasingly, those forces of change have uncovered evidence of an imbalance of power between corporations and their stakeholders. So now would be a great time for Savvy Directors to dive into the topic of stakeholder engagement.

Stakeholder Engagement

The term stakeholder engagement refers to the work that organizations undertake to identify, understand, communicate with and involve their stakeholders.

Effective stakeholder engagement builds trust between an organization and its stakeholders. Organizations benefit by accessing valuable information, creating goodwill, and identifying potential issues. Stakeholders, in turn, benefit by helping the organizations understand their needs.

Stakeholder engagement is not just a nice-to-do or a way to earn brownie points. It’s an essential element of running a successful organization - a way to build trusting, respectful relationships that help them pursue their purpose. Positive stakeholder relationships help them understand their environment, leading to deeper understanding, stronger decision-making, and better risk management.

Lately the concept of stakeholder capitalism has taken hold, with pressure from investors and advocacy groups for companies to focus more on the needs of all stakeholders, not just shareholders. A Diligent Institute study found that companies outside the US face more of this kind of pressure, while in the US, stakeholder capitalism is still controversial. Even so, the study found that most American directors do consider stakeholder interests to be vitally important to their organizations.

Whether or not you call it stakeholder capitalism, there’s widespread belief – supported by research - that an organization’s best interests can’t be considered in isolation from those of its stakeholders.

Prioritizing Stakeholders

All organizations have stakeholders, although who they are varies widely based on its activities – what it does, where it operates, and who is impacted. Stakeholder engagement begins with identifying the organization’s own unique set of stakeholders.

Some organizations have a very long list of stakeholders - employees, unions, contractors, customers, suppliers, investors, regulators, NGOs, governments, pension plan members, special interest groups, media, and the community.

Non-profits may need to add members, clients, families, volunteers, donors, funders, and neighbors.

Of course, not every stakeholder group merits the same degree of attention. Some are far more important to the organization’s success than others. That’s why prioritizing stakeholders is so important. But how? One simple tool is the stakeholder map.

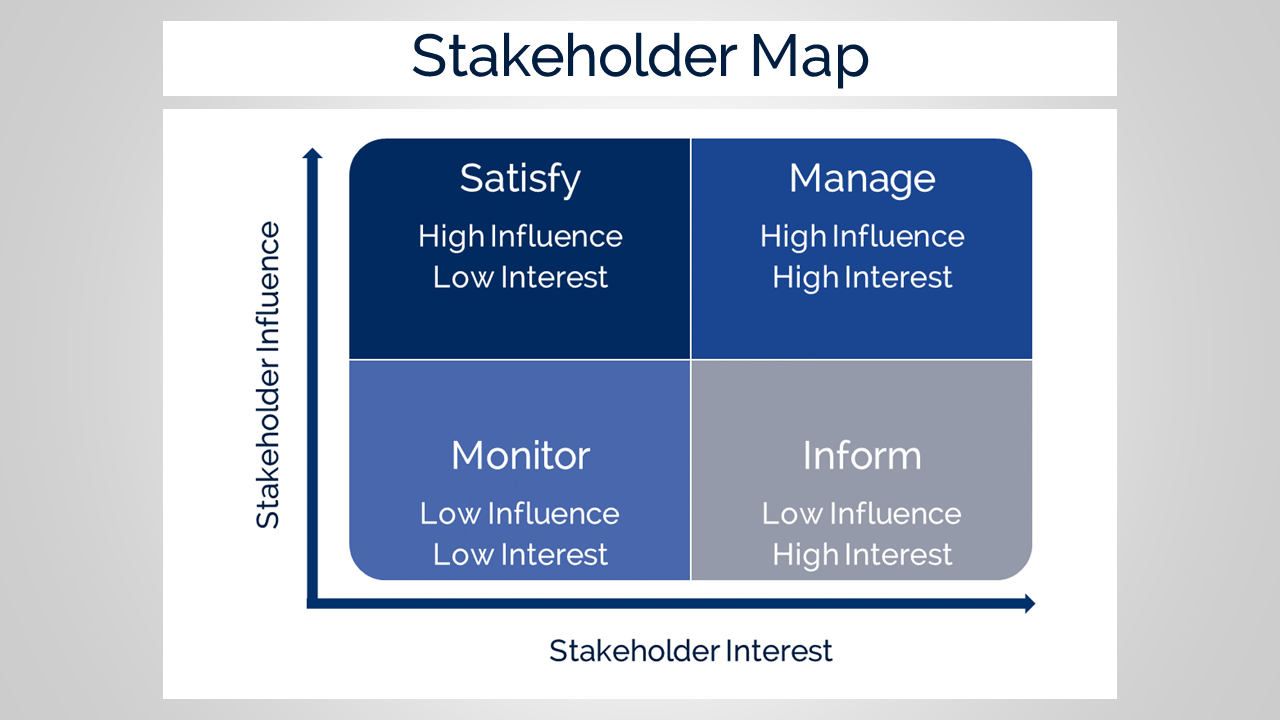

A stakeholder map plots stakeholders on a two-by-two matrix, with influence along one axis and interest along the other. Each identified stakeholder group is then plotted into its corresponding quadrant.

The four quadrants are:

- Satisfy. These stakeholders are highly influential, but they don’t have a lot of interest in the organization and aren’t actively engaged. Still, be mindful of their needs and keep them satisfied, because if they get offside, they can pose a risk.

- Manage. These are your key stakeholders. With a lot of influence and a strong interest in the organization’s decisions and activities, they need to be managed well to build strong relationships and ensure their continued support. Regular communication, engagement and involvement are important.

- Monitor. These stakeholders sit on the periphery. They are not really interested in the organization, nor do they have much influence. Monitor their activity as they could become more relevant over time.

- Inform. These stakeholders have a strong interest in the organization but very little power or influence on it. Anticipate their needs, keep them informed, consult on their area of interest, and use their input where feasible.

A stakeholder map like this is useful because it creates shared understanding, identifies potential risks, and prioritizes stakeholders so engagement plans can be made and resources assigned.

But keep in mind that stakeholders tend not to stay put in one little box. Their level of interest or influence can change gradually over time. Or an external event can cause a sudden change from one quadrant to another.

An example of this kind of a sudden shift is a public sector organization where the local government has a lot of influence (or power) but not much interest. An unexpected event can cause the media, including social media, to sit up and take notice – usually in a negative way. The government’s level of interest will suddenly become very, very high and they will exercise their influence in a tangible way, at least until the tempest blows over.

Although every organization’s stakeholder map is unique, typically you’ll find customers (you may call them clients, users, beneficiaries, or simply the people who receive your services) and employees in the Manage quadrant where key stakeholders are located. Depending on your sector, there are other typical key stakeholders as well, such as investors, shareholders, major donors, or regulators.

In his Forbes article, The Triumph of Customer Capitalism, Steve Denning makes the argument that the primary stakeholder must always be the customer. That does not imply that the organization doesn’t have other stakeholders, priorities and concerns. But it does mean that creating value for customers is the true purpose for any corporation.

“Generating fresh value for customers is the basis for generating benefits for all the stakeholders, not vice versa.” – Steve Denning, Forbes

Employees are another key stakeholder group for any organization. For some time now boards have been taking an active interest in employee engagement, which impacts an organization’s culture, its ability to attract and retain talent, and how it innovates and performs over time. It seems to me that, given labor shortages and intense competition for talent, employees now have an even more powerful voice than before the pandemic.

Some boards have been experimenting with ways to better hear the voice of employees. Representation on the board is one way to do it. This approach is virtually unknown in North America, but it’s more prevalent in other parts of the world and is even required in some European countries. Other ways to hear the voice of employees include designating a director to be employee champion, establishing a workforce advisory panel, or setting up a ‘shadow board’ – an approach that gives up-and-coming leaders a chance to debate issues with the board.

The Board’s Role

Most stakeholder engagement processes occur at the management level as they are in the best position to identify and map the organization’s stakeholders.

For the board, ensuring that the organization has a culture that places a high value on trust in its relationships with stakeholders is a critical component of good governance. To accomplish this, the board oversees the engagement process and confirms that there are strategies in place to identify, prioritize and understand stakeholders.

The board itself must have an awareness of the stakeholder environment and understand their needs and interests. This means that directors need regular access to accurate and independent information about stakeholder perspectives. This usually comes in the form of management reports and presentations – a one-directional flow of information at best. Stakeholder concerns – unvarnished and unfiltered - may not necessarily make it through to the board to support decision-making.

In some circumstances the board may decide it should engage directly with key stakeholder groups. The traditional view is that the process of stakeholder engagement resides with management, while the board provides challenge, oversight and direction. But attitudes are changing, and some experts have suggested that directors need more direct contact with stakeholders and more involvement in stakeholder engagement. There’s no one-size-fits-all approach. Organizations in various sectors, industries and geographies manage it differently.

Some mechanisms to bring the stakeholder view to the board include advisory panels, forums, meetings, consultants, site visits, social media, and townhall meetings. Other innovative governance approaches include seeking insight from regional or advisory boards, establishing a stakeholder committee of the board, designating directors to understand stakeholder concerns, appointing directors with specific stakeholder expertise, and incorporating stakeholder factors into board evaluations.

Questions for the Board

Successful boards have curious directors with a genuine interest in the environment in which the organization operates. Curious directors ask thoughtful, purposeful questions about the perspectives of the company’s employees, suppliers, customers, and other stakeholders. Their questions ensure that the board is well-placed to make informed decisions about the long-term future of the organization and its impact on stakeholders.

Some questions to think about:

- Which groups are vital to the organization’s long-term success? What are their interests?

- Which stakeholder groups are likely impacted by the actions of the organization?

- What is the level of mutual trust between us and our stakeholders?

- Are we getting the right information about stakeholders?

- Should the board engage directly with any stakeholder groups on any particular issue?

- Does our engagement with stakeholders reflect their priority in our stakeholder map?

- How does our decision-making process reflect stakeholder perspectives?

- How are the needs of stakeholders considered by the organization?

- Are we spending enough time on stakeholder issues?

- Do we have the right mechanisms in place to hear and consider stakeholder perspectives?

- How should we communicate decisions to impacted stakeholders?

- Do we regularly review the effectiveness of our stakeholder strategy?

- What independent data do we have to speak to our relations and stakeholder impact?

Your takeaways:

- An organization’s best interests can’t be considered in isolation from those of its stakeholders.

- Stakeholder engagement begins with identifying and prioritizing the organization’s stakeholders.

- Stakeholder engagement is a critical component of good governance.

- The board works to ensure that the organization has strategies in place to identify, prioritize and understand its stakeholders.

- Stakeholder engagement is usually a management process, but in some situations, the board may consider engaging directly with key stakeholders on critical issues.

- Directors can ask purposeful questions to ensure the organization has an effective strategy to build and sustain trusting relationships with stakeholders.

Resources:

- Stakeholder Voices in the Boardroom. George Anderson, Tessa Bamford and Katherine Moos. Spencer Stuart. July 2021.

- 5 Basic Principles for Effective Stakeholder Governance. Australian Institute of Company Directors. May 2021.

- Why Stakeholder Capitalism Will Fail. Steve Denning. Forbes. January 2020.

Leave a comment below to get in on the conversation.

Thank you.

Scott

Scott Baldwin is a certified corporate director (ICD.D) and co-founder of DirectorPrep.com – an online hub with hundreds of guideline questions and resources to help prepare for your next board meeting.

Share Your Insight: Who would you identify as key stakeholders for your board to pay attention to?

Comment